GMP

Introduction

We all know that Golang has high concurrency performance, thanks to its excellent GMP model design. This article discusses the cleverness of the GMP model.

History

Single process

In the early days of operating systems, there was only one core, and computers executed tasks in the order they were arranged, with task A executed before task B, and task B executed before task C. When task B (actually a process) was blocked, it had to wait indefinitely.

Multiple processes

Imagine that we now need to write a web crawler to retrieve 100 pages, and each page takes 1 second to respond. The entire process takes more than 100 seconds (processing data, writing to a database, etc.), so multi-process/multi-threading technology was introduced. When a task is blocked by I/O, the CPU switches to execute other tasks, and then returns to execute the original task when the other tasks are completed. Compared to the initial performance, this approach greatly improves performance, and the CPU is no longer idle, achieving so-called “concurrency,” but not “parallelism.”

Multiple processes on multiple cores

With the development of hardware technology, computers have entered the era of multiple cores, and multiple CPUs can work simultaneously. At this point, we can say that it is parallelism. However, processes consume a lot of resources, and the cost of switching processes is high:

- Save context: CPU registers, program counters, process status, etc.

- Load new context: Load new context into CPU registers and program counters.

- Switch memory space: The memory space between processes is independent, so when switching processes, the operating system needs to switch the memory space of the process.

- Switch hardware context: such as IO cache, interrupt vectors, etc.

The most common approach is to use multi-threading technology. Since all threads in the same process share the same memory space, file descriptors, and global variables of the process, when switching threads, only the context information of the thread itself needs to be switched, and the memory space and other resources of other processes do not need to be switched.

However, multi-threading also brings new problems: in order to ensure data safety when multiple threads compete, mutexes and other synchronization mechanisms need to be introduced, which significantly increases the cost of mutual exclusion behavior.

Goroutine

Since thread and process scheduling are relatively resource-intensive, engineers later discovered that a thread is actually divided into kernel mode and user mode, and named this user mode thread a “goroutine,” meaning a lightweight thread. When encountering I/O blocking, we can implement scheduling processing in user mode ourselves, without having to trouble the lower-level operating system to switch threads to schedule. This significantly improves performance because a process occupies approximately 4 GB of virtual memory (32-bit operating system), and a thread also requires approximately 4 MB. However, a goroutine is much smaller, requiring only a few kilobytes in Go.

Binding relationship

N:1

N goroutines are bound to one thread, avoiding the hassle of thread switching, but multiple cores cannot be used to process programs.

1:1

One goroutine is bound to one thread, returning to the kernel to switch threads.

M:N

M goroutines are bound to N threads, which can fully utilize multiple cores to efficiently process programs, but the difficulty is to implement the binding and scheduling of goroutines and threads in user mode. Go language uses this strategy.

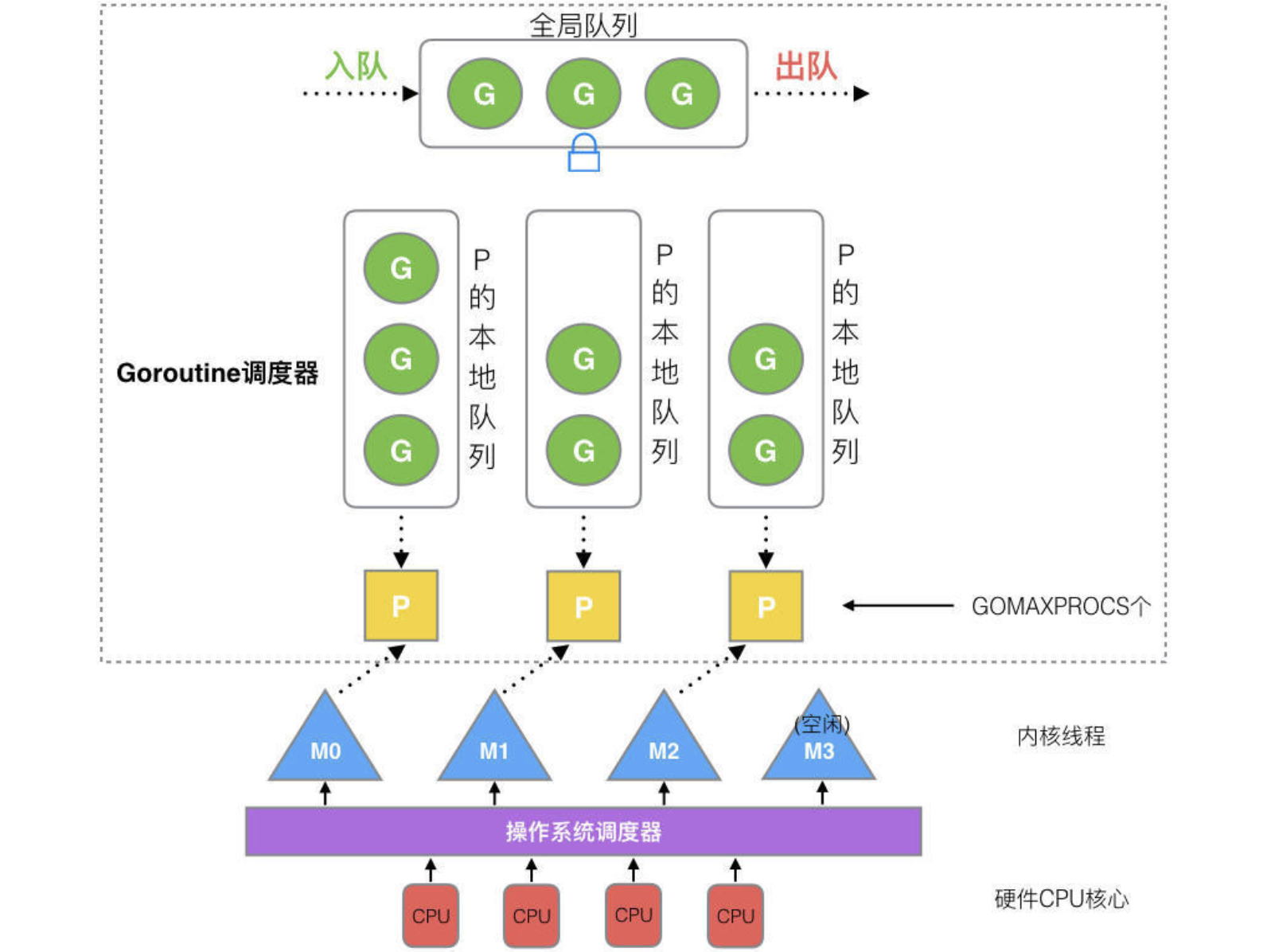

GMP Model

G:Represents goroutine

M:System thread

P: Scheduler

source code runtime/proc.go

1 | func findRunnable() (gp *g, inheritTime, tryWakeP bool) { |

Each P has its own queue for storing goroutines to be executed, and there is also a global queue. When there are no goroutines to be executed in P’s own queue, it first steals some from global P queue. If global P queue is also empty, it will take goroutines from the other queues using the method mentioned above. When taking G (referring to goroutine) from the global queue, it will not take many at once, otherwise, other P will come here to take them, increasing unnecessary overhead.

The GMP scheduling method is as follows:

- A system thread (M) that wants to execute a goroutine must first bind to P

- M takes G from P to execute it, and then takes the next G according to the aforementioned method

- If M encounters a system call (such as file read and write) while executing G, P will unbind from M, but M will remember which P it was bound to. When G and M exit the system call, they will find the P that was just bound to this M. If it cannot be found, they will find other P. If it cannot be found, the G will be marked as runnable and placed in the global queue.

In addition:

- If a running G1 creates a new G2, G2 will be bound to P1, where G1 was originally located.

- Rule: When creating G2, running G1 will wake up other P and M (assuming P2 and M2) to execute tasks in the system.

- If there are no Gs in the queue of P2, it will try to steal some from other places using the aforementioned method. If it still cannot find any, it will keep searching. We call this state a “spin state.” Although it seems a bit silly, it is still acceptable compared to the overhead of creating and destroying threads.

In summary, the GMP model uses lightweight goroutines to reduce resource consumption and increase concurrency, and uses a clever scheduling strategy to avoid the high overhead of thread and process switching.